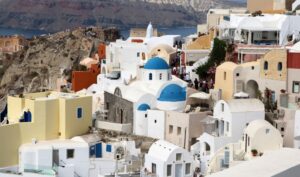

Good wine needs no wreath, the saying goes, but these wines have it before the grapes even start to grow. The mega volcanic eruption around 1630 BC laid a shroud of pumice, sinters and ash over this once beautiful island. But anno now, a metamorphosis takes place here every year that resonates worldly. Welcome to the Greek wine island of Santorini.

MAY ON SANTORINI

May on Santorini. Pile walls of lava rocks curve around the fields and embrace the precious earth. Christóphoros Vamvakousis lives amid his vineyards, which are flourishing. Volcanic ash rains covered the island around 1630 BC with up to 60-metre-thick, now encrusted deposits on which no blade of grass will grow. The mix of ash, pumice, sinters and lava bombs here is called áspa or Theran earth, earth of Thera, an ancient name for Santorini.

PHYSICAL FACTORS

But people learned to make the soil productive and turned it to a depth of 50 to 65 centimetres. As it turned out, the now powdery layer absorbs rain and dew like a sponge. Even in summer, it is moist at 3 to 4 fingers below the surface to a hard, impermeable layer at a depth of 50 centimetres. This also explains the large number of surface roots: everywhere the vine seeks its water. Thus, under ideal conditions, the plant has sufficient moisture all year round.

However, not always the weather cooperates over the Aegean Sea, in which also

Santorini is located. Most rain falls between October and February with an annual average of less than 400 millimetres. However, with lows of 130 millimetres, the vine also suffers, which can survive on 200 millimetres a year. Christóphoros lets the earth slide loosely through his hands. 'Look, the distance between the plants is important: it should be 1.80 metres. The uptake of water and food determines productivity.'

CLIMATE

Viticulture on Santorini depends on three physical factors: soil composition, climate and grape variety. Over the years, viticulture here has grown into a

lucrative form of livelihood, almost the only form of arable farming on Santorini that thrives without irrigation. Rising sea winds against the up to 300-metre-high crater rim sweep across the island at night, an extraordinary spectacle of mysterious mists. In the morning, dew lies on the vine leaves. From mid-June onwards, this continues throughout the summer. After sunrise, the vapours dissolve quickly. The summer winds, locally called Meltémia, give fungi (peronospora or Botrytis) little chance. The Meltémi winds blow from early May to mid-September.

WINE FOR WATER

Grapes and sultanas have always been used as fruit and kept for the difficult winter months and for sea voyages. Wine was the drink of choice for soldiers and sailors in ancient times. At

lack of drinking water and a safe harbour, the island of Santorini was unattractive for sailors to visit. Nevertheless, it became an important stopover on Venice's journey to Crete and the Middle East, according to Venetian archives. The reason: a wine culture prevailed here. And wine apparently counted more heavily than water. The sweet wine was highly sought after: Malvasía, or Malmsey, from sun-dried grapes. In 1657, Jesuit and papal envoy François Richard wrote in Paris about Santorini's wine, as did French traveller Jean de Thévenot. The vine is good

resistant to drought.

Text & Photography Douwe Laansma

Curious about the full article? You can read it in the latest Winelife edition 69. Order this one here!

Don't want to miss a single edition? Subscribe then subscribe to Winelife Magazine now!

Want to stay up to date with the best articles? Follow Winelife magazine on Instagram, Facebook and sign up for our fortnightly newsletter.